Why Fungi Are The Future

The misinformation and stigma surrounding fungi only exacerbates the public’s view of them as disgusting and dangerous. But could there be more to them than meets the eye?

Poking through the moss after a spring shower. Popping up in your pristine front lawn despite your father’s unrelenting efforts to get rid of them. Lurking under carpets of waving grass and tangled in the thick stench of rotting earth: Tiny white buttons, startling scarlet caps, paper-thin umbrellas- and the keys to humanity’s future. Yes, you read that right.

Fungi are truly everywhere. The vast majority of all plant species depend on symbiotic relationships with fungi (called mycorrhizal relationships) to survive, mold species such as penicillin have formed the basis of modern medicine, and lichen (made up of a symbiosis between a fungus and algae or cyanobacteria) covers almost 8% of the earth’s surface and can live for thousands of years. Yet the incredible social stigma surrounding fungi- specifically, mushrooms- has existed for centuries, much farther back than mycology, the study of fungi, has even had a name. Mushrooms have been seen as repulsive: slimy growths of darkness and decay, oozing into existence out of nowhere for no discernible reason or purpose only to vanish just as quickly as they appeared. Not only that, the LSD craze of the 60’s only worsened society’s view on mushrooms, as nowadays the very word conjures up images of drug-addled hippies and psychedelic visions. But the truth behind fungi is far more dazzling than any stereotype or myth could offer- and by unravelling the mystery behind these fascinating organisms, we are discovering countless new methods and innovations to protect our planet.

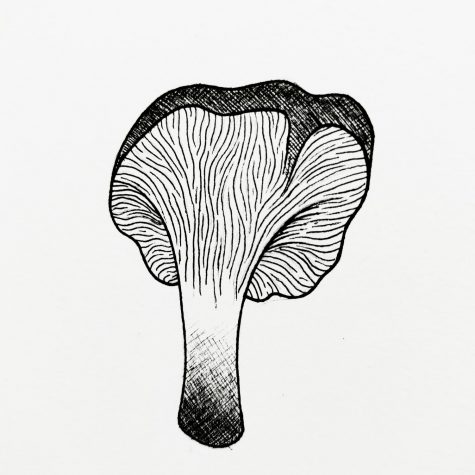

A common misconception is that fungi are, or are at least similar to, plants- after all, they both grow from the ground and stay in one place. However, fungi actually have much more in common with animals, and provide many extremely vital services to the environment. But to understand how fungi work, we first have to understand their basic structure. Mushrooms, contrary to popular belief, are simply the fruiting body of a much larger underground structure called the mycelial network. A mycelium is a complex network of branching strands that works its way through substrate and breaking down materials to absorb their nutrients, digesting them from the outside in. To reproduce, this network fruits by sending a mushroom up to disperse its spores. This is how fungi can become some of the world’s largest and oldest organisms- a single honey mushroom network in Oregon spans over two thousand acres and is between two to eight thousand years old!

Although fungi can sustain themselves through parasitism as well as through mycorrhizal relationships with plants, their primary ecological role is of decomposers: without fungi, nothing on earth would rot, and the soil would be devoid of organic material or nutrients. Because fungi have existed and been continually evolving for what is thought to be as much as a billion years (and have survived five mass extinctions), over time some species of fungi have gained remarkable abilities to break down toxins and heavy metals. Recent studies have shown oyster mushrooms can not only live off cigarette butts and used diapers, but can produce perfectly healthy mushrooms from them! Even more amazing, researchers are working on using fungi to clean up oil spills and filter polluted water through a process called mycofiltration. In mycofiltration, bags of wet mulch are seeded with mycelium, then placed along drainage sites. This method has been shown to clean water of heavy metals and harmful bacteria such as E. coli.

However, knowledge and use of the benefits of fungi goes back much further than our use of them for conservation, and even dates back to times before humanity itself. As stated earlier, most plants depend on fungi and the nutrients they can provide through mycorrhizal relationships to survive, and when plants first evolved to grow on land, fungi served as their root systems for 50 million years before plants evolved their own roots. Some plants even parasitize fungi, such as the ghost pipe, a nonphotosynthetic plant common to Virginia. Not only that, a lot of animals have formed unique relationships with fungi as well, such as leaf-cutter ants, which cut and harvest leaves to cultivate a fungus that in turn, and termites, which similarly cultivate a type of white rot fungus to help digest wood. Humans have also found a staggering amount of uses for fungi, from medicine to building materials to clothing. For example, amadou, or the tinder fungus, was not only widely used as a fire starter by ancient humans (Ötzi, the 5,000-year-old ‘iceman’ famously preserved in a glacier in the Italian Alps, was discovered to have been carrying preserved amadou), but can be made into a fabric resembling felt and used to make hats. Nowadays, a new fashion is on the rise: mushroom leather, which is made from mycelium, is renewable, biodegradable, water and fire resistant, and can be stronger than concrete. Although these facts may be surprising to some, certain kinds of mushrooms have been known to break straight through asphalt, and one statistic states that if a strand of hyphae- the cellular structures that form mycelium- was scaled to the size of a human hand, it could lift a school bus.

It is impossible to write an article on fungi without addressing the elephant in the room- or rather, the elephant in the mushroom- of the widespread use of hallucinogenic mushrooms. Some theorize that humans have been using psilocybin mushrooms recreationally since the dawn of our species; one hypothesis postulates that the effects of psilocybin on the human mind were what allowed us to progress as a society, accounting for the rapid progression of religion and art in a very short time period. Even the story of Santa Claus has basis in hallucinogenic mushrooms: the Sámi people of northern Scandinavia observed reindeer guarding stashes of red and white mushrooms in the snow to later eat, and told stories of a magical man in a sleigh pulled by reindeer, delivering gifts of strange mushrooms beneath the pine trees. But what the Sámi didn’t know was that psilocybin, the psychoactive chemical in ‘magic’ mushrooms, could very well be the key to humanity’s collective mental health. Psilocybin therapy is a revolutionary new technique that is being tested to treat illnesses such as depression, anxiety, PTSD, and OCD, and the results so far have been astounding. A single dose of psilocybin in a controlled and professional environment can have effects on a patient for years, causing them to change their overall mindset on life entirely, and in some cases alleviating symptoms almost permanently. This is because psilocybin allows the brain to make new connections and basically restructure the way one’s mind works, something that other techniques fail to do.

In terms of understanding, mycology is an incredibly new science. Up until very recently it was regarded as a trivial study and lumped in with other fields such as botany, and the vast majority of important figures in the mycological world have started as amateurs with no formal education on fungi. Just a glimpse into the world of fungi has left us with both amazing discoveries and a multitude of unanswered questions. There is still so much to explore, and if these fascinating ideas and discoveries are any indication, fungi might very well save the world.