What Is Line 3 and Why Are People Protesting It?

The history of the Anishinaabe tribes’ fight against Minnesota pipeline and what is at stake

Lorie Shaull, CC BY-SA 2.0

“Protect our water” declares a sign stuck in the thick Minnesota snow.

On long stretches of snow-covered ground in northern Minnesota, lie stacks of steel tubes, cranes, and excavators. Spread around the construction site are protestors with signs and flags emblazoned with the words “Stop Line 3!”. It is the name of an Indigenous led movement fighting against the tar sands pipeline currently being built in the region. The Anishinaabe tribes and climate activists have been protesting the pipeline since 2013, although construction did not begin until November of last year. Over the past few months, support and coverage of the protests has grown with the inauguration of the Biden administration.

President Biden has promised to tackle climate change and “Build Back Better” with green energy, and has made steps towards those goals. After issuing an executive order on his first day in office, cancelling the Keystone pipeline, supporters of Stop Line 3 asked the administration to also call off construction in Minnesota. On March 9th, over 350 organizations signed a letter to President Biden, urging him to act by suspending or revoking the federal permits required to construct: “We urge you and all federal leadership to stand firm against the Line 3 pipeline and act now to halt its construction. The pipeline’s construction is an urgent threat to the waters of Minnesota and Lake Superior, as well as to our global climate.”

The current protests are against the construction of a second pipeline. The first Line 3 was built over fifty years ago in the 1960s, and spans from Edmonton, Alberta to Superior, Wisconsin. As decades have gone by, the pipeline has corroded and ruptured. In 1991, the deterioration of line led to the largest inland spill in U.S. history. According to the Stop 3 Line website, the incident led to “over 1.7 million gallons of oil” to be spilled and contaminate parts of the Prairie River near Grand Rapids. Now Enbridge, the Canadian oil company in charge of the pipeline, wants to abandon the old Line 3 and build a new one along a similar route.

Enbridge first announced plans for the new Line 3 in June of 2013 and applied for a land permit the following year.

After the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission (MN PUC) granted the permit in 2015, one of the first marches against the tar sands pipeline took place in St. Paul. Later that year, the Minnesota Court of Appeals overturned the permit granted by the MN PUC and ordered that an environmental impact statement be made. Protests continued and Enbridge ultimately canceled the pipeline in August of 2016. However, this decision was reversed after Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the National Energy Board (NEB) approved Line 3 at the end of year. Between 2016 and 2018, the environmental impact statement from the MN PUC was released, the permit for the pipeline was granted, and resistance camps were set up near planned construction sites.

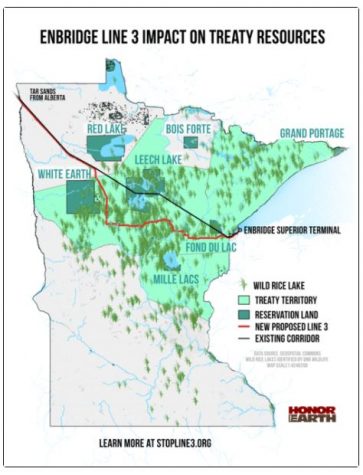

The Stop Line 3 movement has stated a number of reasons for its opposition to the pipeline. Primarily, construction of Line 3 violates the sovereignty of the Anishinaabe tribes, located in the northern U.S. and Canada. The state of Minnesota does not have jurisdiction within reservations nor the consent of all the Anishinaabe bands in the area to build a pipeline through the land. Even off reservation, the tribes have some property rights. The Stop Line 3 website states that these include the right to “hunt, fish, gather medicinal plants, harvest and cultivate wild rice, and preserve sacred or culturally significant sites”. Possible spills would damage ecosystems and hurt the tribes’ ability to practice these rights, which are guaranteed to the tribes through treaties with the U.S government. Line 3 endangers natural and cultural resources within treaty areas established in 1842, 1854, and 1855.

The threat Line 3 poses to the environment has also led to many conservation and climate organizations to become involved with protests. According to the Stop Line 3 website, building the new pipeline “would be roughly equivalent to building 50 new coal fired power plants” due to the amount of electricity required to run the line. Aside from protesting the new Line 3, Indigenous and climate advocates are calling for the old pipeline to be removed and encouraging the state of Minnesota to pursue renewable energy.

Winona LaDuke, an Indigenous activist and the former vice presidential candidate for the Green Party in 1996 and 2000, has been a prominent leader in the Stop 3 Line movement. In a interview with the Rolling Stone, she emphasized that the spread of COVID-19 is additional danger that construction of the pipeline poses: “There is certainly no reason, in the midst of a COVID virus, to bring forty-three hundred workers into the state of Minnesota–into remote communities that are high risk and have no exposure.”

Other Minnesotans support the pipeline. The organization “Minnesotans for Line 3” has argued that building the pipeline will create local jobs and power the economy. Stop Line 3 has countered this by arguing that the old pipeline should be removed instead, which would also provide employment.

Going forward, the Stop Line 3 movement faces an uncertain future. Construction on the pipeline is still in progress, despite attempts to block it. However, the movement has seen some progress this week. On Tuesday, March 23rd, the Minnesota Court of Appeals heard arguments from several Indigenous and environmental groups, along with the Minnesota Department of Commerce. The court will not issue a decision until June. In the meantime, the Anishinaabe tribes and other environmental protectors will continue to spread awareness and “Stop Line 3!”.